News Archive Articles from MESD News and Other Sources

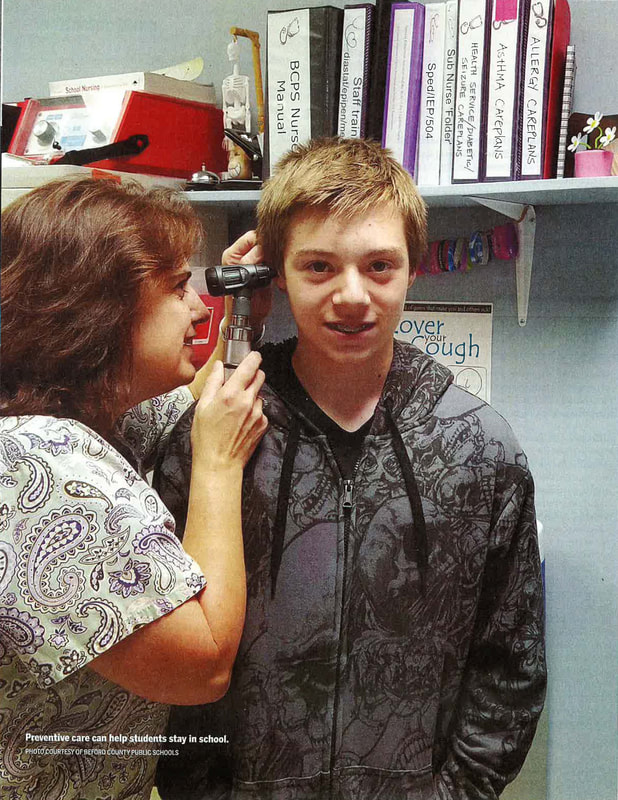

Critical Care: School Nurses Face an Increase in Students with Acute and Chronic Health Issues12/1/2016 The new school year was just days old, and school nurse Nina Fekaris already had attended to a case of head lice and two bee stings. Routine stuff for a registered nurse with 30 years of experience, but a mere drop in the bucket of Fekaris's workload. Fekaris provides nursing care to approximately 4,000 students in four different schools in the Beaverton School District near Portland, Oregon. Her duties include developing individual health plans for students who have chronic and acute health conditions such as diabetes, asthma, life-threatening allergies. seizure disorders, and mental health and behavioral issues. Her charge: to keep her students healthy, safe, and on task in school. She monitors immunization records; makes referrals for students in need of vision, dental, and medical care but without their own health providers; and conducts health education lessons. She trains and delegates tasks to secretaries, administrators, and other nonmedical school staff to dispense medications, insert urinary catheters, administer anti-seizure suppositories, and respond to cases of anaphylaxis and other emergencies when she is not in the building. As one of 13 registered nurses (RNs) employed by Beaverton to provide care to 40,000 students (anoth- er nine provide direct nursing to students in need of individualized, special care through the special education department), "chances are really good I wouldn't be in the building when there is an emergency;' Fekaris says. CHRONIC CONDITIONS At a time when the nation's student population has become more medically complex and diverse, Beaverton, like many districts, faces challenges when it comes to providing nursing services. At the center of these challenges is "limited school funding," says Danielle Sheldrake, Beaverton's executive administrator for student services. "Often what we're looking at is: Do you fund a classroom teacher or do you fund a school nurse?" Studies indicated that 15 percent to 18 percent of the nation's 50 million K-12 students have a chronic health condition. According to the National Institutes of Health, nearly 9 million students have asthma and about 13 million are overweight or obese. Five million (1 in 5) have some type of serious mental illness - from ADHD to anxiety to depression - the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports. In surveys, school nurses say they spend 32 pe cent of their time on mental health issues, says Beth Mattey, president of National Association of School Nurses (NASN). Often the problems "manifest as physical ailments, such as stomach aches or headaches, and the first place students go is to the school nurse," she says. Only 45 percent of the nation's public schools have a full-time, on-site nurse; 30 percent have one who works part-time, often dividing his or her hours between several school buildings; and 25 percent have no nurse at all, according to NASN data. This imbalance comes at a cost, Mattey says: "We have to recognize that health and education are linked. If a child is not healthy or doesn't feel well, [he or she is] not going to be learning in the classroom." The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) echoed that sentiment in May when it updated its recommended school nurse policy and called for a minimum of one full time RN in every school. Previously, the group had endorsed a ratio of one RN to 750 students in the general student population. The new policy says "the use of a ratio for workload determination in school nursing is inadequate to fill the increasingly complex health needs of students." With a ratio of one nurse for every 4,664 students, Oregon has one of the worst in the country, says Fekaris, who is chair of Oregon's governor-appointed school nursing task force and NASN president-elect. The state's funding problems started in the 1980s when property tax measures reduced money for schools, she says. Now, with more and more students in school with chronic and acute medical and mental health conditions, the situation has come to a head. Out of 197 school districts, 79 (40 percent) do not provide any nursing services, leaving almost 30,000 students with no access to a school nurse, according to the task force report, released in September. CORRECTING THE PROBLEM Like Beaverton, Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools has documented a significant increase in demands placed on school nurses and is aggressively trying to correct the problem. Data collected over the last 10 years show "an 85 percent increase in the number of students diagnosed with chronic health problems or complex medical needs, just in our community;' says Tony Majors, chief support services officer for the 88,000-student district. In one school year alone, the nursing staff had more than 40,000 office visits with children and administered nearly 80,000 procedures to help kids with complex medical needs such as asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, sickle cell, diabetes, and seizure disorders stay in school. Work performed by Nashville's school nurses - who are, in fact, employed under a contract with the Metropolitan Nashville Health Department- overwhelmingly consists of providing medical treatments ordered by physicians, Majors says. With a budget that allows for just 62 registered nurses to cover 140 district schools (50 schools were found to have little to no access to a nurse), there's little time to provide "general supportive health services" for the cuts and bruises and ailments that regularly come up in a student population, Majors says. Teachers and front office staff are left to handle those cases, impacting their productivity. Designated school employees are trained by central office coordination teams in medicine dispensing and safety protocols, including first aid, CPR, and the use of an EpiPen (for treating anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction) and an AED (automated external defibrillator) for treating cardiac arrest. Along with lost productivity, a shortage of school nurses also is associated with increased student absenteeism. In its new policy, the AAP says that having a registered nurse on the school campus allows for more accurately assessing whether a student needs to go home or can stay in school and learn. Although Nashville has made "some systemic investments" in nursing services in each of the last three years, the result has been "small, incremental increases in the number of nurses added;' Majors says. A joint proposal by the school system and the health department for funding to put a nurse in every district school was rejected by a mayoral review committee in March. It would have raised the district nursing budget from $4.5 million to approximately $12 million over four years. Since then, Nashville Mayor Megan Barry has funded "a best practices analysis" to examine what an expanded health investment plan would look like for the school system. With that analysis, the district will present a new proposal that takes into consideration factors such as increased care coordination; more time for student assessments, referrals, and follow-ups; and improved maintenance of student health records. One possible proposal comes with a $3.5 million price tag over three years and would have a full time nurse at every traditional high school and a nurse shared between every middle school and its feeder elementary. "That's getting you close to a 2-to-l ratio, and because of the size of the elementary and middle schools, the nursing staff could accommodate both the procedural care and the general health needs," Majors says. GROWING A NURSING PROGRAM Practicing austerity "when you can practice it" has guided the Corpus Christi Independent School District, says board trustee John Longoria. But having a registered nurse at each of the 60 campuses in the South Texas district has been deemed a priority, particularly because of the student population served. The school district attracts families from "all the way down in the [Rio Grande] Valley, up to San Antonio and Houston," says health coordinator Angie Guerrero. Many of those who migrate to the area have children with "quite a few complex medical needs: can cer, renal failure and dialysis, uncontrolled seizures, tube feedings, diabetes, and obesity;' she says. "It's not like in the [past], when maybe all you had to do was check for a fever," Longoria adds. "The health issues that a child brings to school are more complex, and you need to have that skilled nurse to work through the problems and have one at every school." For some students in the district, "the school nurse may be the only medical professional they see in a year's time," he says. Bedford County Public Schools, a 10,000-student district in southwest Virginia, is well acquainted with the struggles and benefits of growing a nursing program. Before a grant from the Bedford Community Health Foundation kick-started the Bedford School Nurse Initiative in 1998, the district employed just three school nurses in its 19 schools. With the grant and matching community funds, the district was able to place a part-time registered nurse in each building. With continued funding, the district has converted the part-time positions into full-time, ensured coverage for every school, and added back-up nursing support and a nurse who works one-on-one with a student needing specialized help. Getting to this staffing level "was a long, hard process" that required earning community support through outreach, involvement, even media cover age about nurses' work in the schools, says nurse supervisor Patricia Knox. "We had to show the documentation and data about how we do change student outcomes by keeping students in school, improving their attendance, and helping them be successful;' she says. Bedford also has seen its share of chronic conditions increase among students. Adequate staffing, however, has allowed the nursing team to provide procedural care and fit in prevention and intervention efforts, along with education programs. "On a typical day in some of our larger schools with 600 to 1,400 students, the nurse's clinic will see on average 50 to 70 students;' Knox says. The key focus is on "managing students, as far as do they need to go home or can they stay," she says. "If we really want to assist them with their academic success, we want to turn that clinic time around right back into class time, if that's where they need to be." If there's concern about a possible contagious or communicable disease, of course, they should not be in school. School nurses are "the first line of defense" when it comes to identifying and limiting the spread of diseases, Knox says. Mattey notes that it was that kind of vigilance that helped alert health officials to the H1N1 "swine flu" outbreak in 2009. Mary Pappas, a school nurse in Queens, New York, is credited with being the first to notify state and federal health officials to the outbreak after escalating numbers of sick students began showing up at her office with flu-like symptoms. OUTSOURCING OPTIONS

Akron Public Schools has looked to private sector vendors to meet its nursing services for more than a dozen years. It currently contracts with Akron Children's Hospital to supply a trained health aide in each of the district's 54 schools, along with three RNs who provide supervision and support, and rotate throughout the district. Two additional registered nurses provide management, training, and staff hiring, says Debra Foulk, Akron's executive director for business affairs. The health assistants and RNs are insured by the hospital's insurance coverage, removing the school district from that liability. The hospital also handles screening and background checks. The partnership has been successful in terms of both the quality of staff and additional services provided, Foulk says. One example: The hospital created an online diabetes-care training course to meet Ohio state law that allows nonmedical school staff to be trained to assist students with insulin administration and, in an emergency situation, to administer glucagon. Health aides can perform first aid and CPR, handle medical records and administrative tasks, measure vital signs, administer physician-ordered medication, and conduct required eye and vision screening tests. They cannot, however, perform many of the duties of an RN, e.g., administer vaccinations, interpret clinical data, and do assessments to plan and coordinate care. Health aides also must work under the supervision of a registered nurse. (Approved duties for health aides, nursing assistants, licensed practical nurses, and licensed vocational nurses vary state-to-state.) Even with the more limited "scope of practice," the health aide program, in conjunction with RN supervision, works well for the district because. it provides much needed services and support, says Akron school board President Bruce Alexander. "And by partnering with Children's Hospital, one of the best children's hospitals in the country, it allows our students, if they need additional medical attention, to get those services and for families to get connected to other important services," Alexander says. "It helps our school district all around." Recommendations that the best option in a school setting is an RN in every building have to be considered against "the reality of what the funding can afford," Foulk says. Akron's $925,000-a-year nursing services contract "is not cheap," she adds. Unlike some other school services, there's no federal or state funding to offset this expense, she says: "School meal programs get some federal funding. Transportation might get some state support. But there's no state funding for this. It is strictly carried by our local general funding. But we feel it's that import ant that we are wanting to set aside (money) for this, because students don't learn if they don't feel good. In October, the first school-based health clinic in Akron opened at the district's North High School. It is operated by the nonprofit group Asian Services in Action, Inc., with support from Akron Public Schools and Summit County Public Health. The clinic will not replace the regular nursing services available to students at North High, Foulk says. Instead, it is intended to provide separate, more comprehensive care. Services offered will be directly billed to a student's public or private insurance carriers and a sliding-scale payment system will be available for those without insurance. Insurance payments as a potential funding source to help put more nurses back into Oregon schools is one of the recommendations highlighted in the state's task force report. It urges the immediate creation of "the necessary infrastructure and staff to support increased school district Medicaid billing" for health services provided to eligible children. "It shouldn't all be education dollars or general fund dollars that pay for nursing services in school buildings;' Fekaris says. More than ever, "we're providing primary, secondary, and tertiary public health care in our schools for our most vulnerable population - our kids:' Michelle Healy ([email protected]) is American School Board Journal's staff writer.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Filter Posts by Topic

All

Filter Posts by Date

February 2024

|

|

|

About

|

News & Trainings

-:- More Events -:-

|

Schools

|

Programs

|

Services

|

|

Our Districts

|

For Parents

|

Staff Resources

|

Contact

|

|

|

Multnomah Education Service District prohibits discrimination and harassment on any basis protected by law, including but not limited to race, color, religion, sex, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, mental or physical disability or perceived disability, pregnancy, familial status, economic status, veterans' status, parental or marital status or age. For more information and detail on MESD's non-discrimination policies, including procedures and contact information for reporting discrimination, please visit the MESD Non-Discrimination, Harassment & Bullying Notice page.

|

Multnomah Education Service District is in the process of making its electronic and information technologies accessible to individuals with disabilities. If you have suggestions or comments please contact the Office of Strategic Engagement: 503-257-1516. For more information, visit the Collaborative Accessibility page.

|